Juan Camilo Serpa: “We are building the LinkedIn of sustainability”

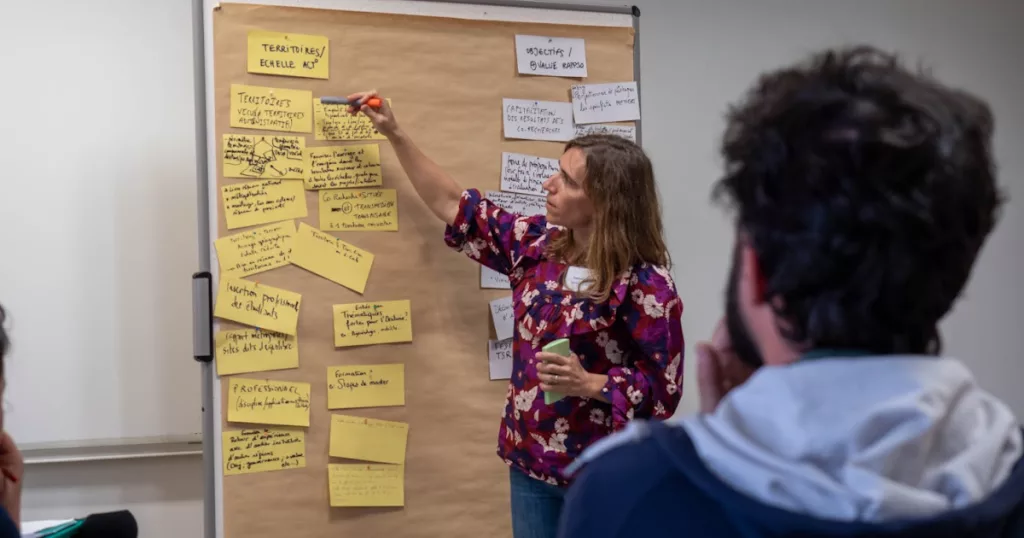

The Sustainaibility Academic Network, SusAN in short, has been launched in March 2025, to create an online discussion and collaboration space for scientists who are concerned with sustainability